Saying yes is easy.

Saying yes makes other people happy, which makes you feel good. (Helping others literally releases “happiness chemicals” in our brains.) By nature, humans are social creatures. We like to help others when we can.

But saying yes also comes at a price.

As artist, entrepreneur, and self-professed people pleaser Ben Toalson observed:

The problem with [saying yes too often] is people will take you up on it without consideration for how taxing that is for you. It's not others' responsibility to know what you can take on.

It's not up to other people to know how busy you are.

We need to start thinking differently about what it means to say no. Rather than viewing it as disappointing others, think of no as an instant time maker:

Toalson’s podcast co-host and designer Sean McCabe summarized it this way:

While no can be a hard word to say, it’s the only tool we have for creating more time. Yes fills time. No makes time.

If you consider everything you possibly could be doing at any moment, you'll realize there are always more opportunities than we can take hold of. We're lucky that there are so many productive, fun, motivating ways to spend our time.

But it's unrealistic to think we can do everything.

Saying no is an uncomfortable yet necessary part of maintaining priorities and making meaningful progress toward our goals. It's the magic power we all have for making more time in our day.

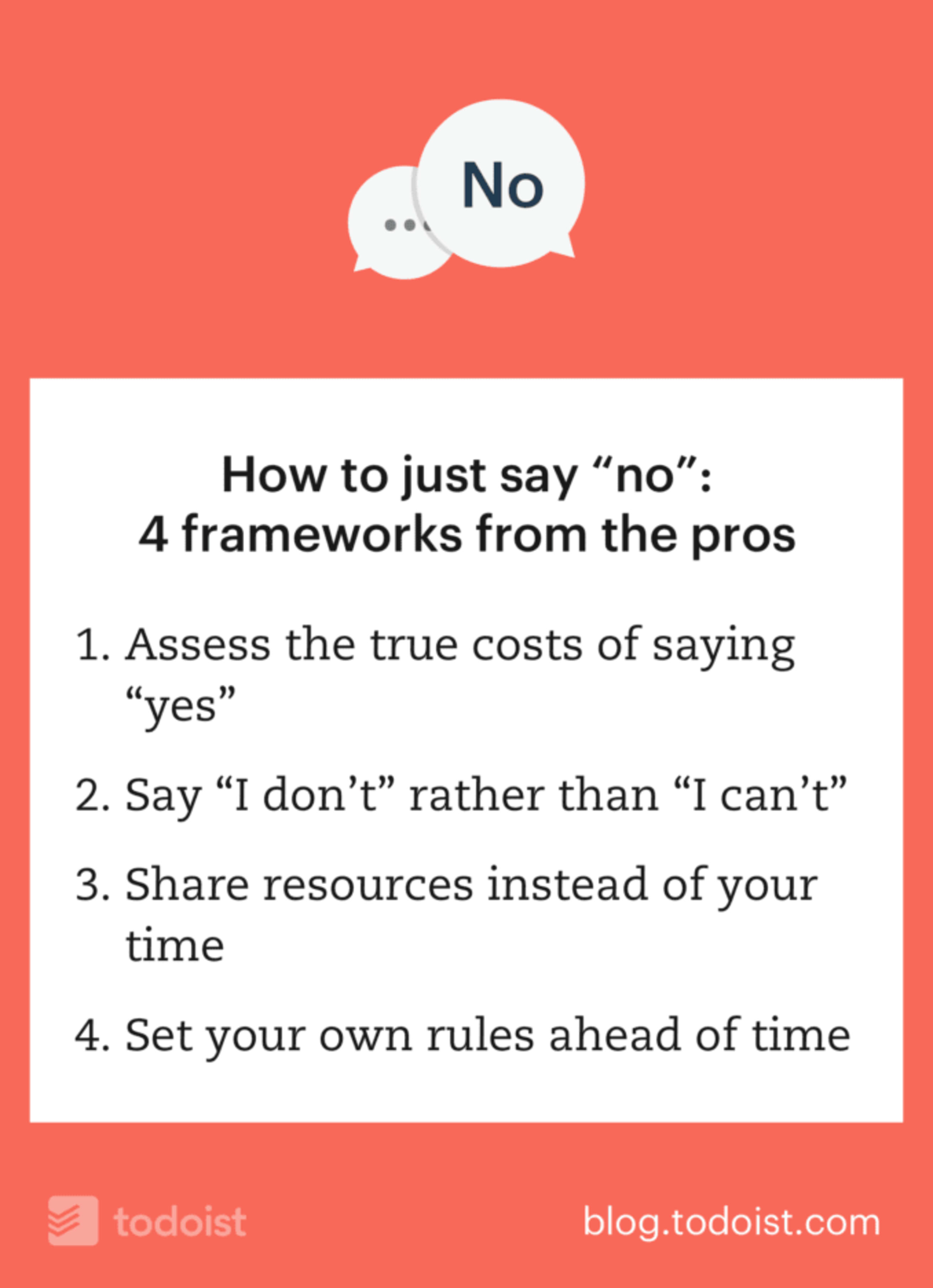

Only you can decide what to say no to, but I can help with the how. Here are four different approaches to get more comfortable with saying no and making more time in your day.

Assess the true cost

The first step is to be honest with yourself about what saying yes really means.

Author Kevin Ashton quotes fellow author Charles Dickens, who was often confronted with the exact kind of request that makes saying no so hard:

'It is only half an hour' — 'It is only an afternoon' — 'It is only an evening,' people say to me over and over again; but they don’t know that it is impossible to command one’s self sometimes to any stipulated and set disposal of five minutes — or that the mere consciousness of an engagement will sometime worry a whole day.

It can be incredibly difficult to turn down a request for just five minutes, or only a short call. But Ashton reminds us to evaluate the true cost of these requests.

Is it ever truly just five minutes? Or 15? When I ask someone for 15 minutes of their time, I'm always mindful of the clock as we speak, but even so these short meetings inevitably run a bit long. It's almost impossible to make a meaningful interaction fit into such a small chunk of time.

These requests usually come with good intentions, but it's up to you to decide what the cost will really be when you say yes. As Dickens said, there are often hidden costs to opportunities we say yes to. A 15 minute meeting might actually stretch to an hour once you get going. But what about the time to get to the meeting and back to your office? What about preparation time? And the time to set up the meeting in the first place?

Most importantly, what about the mental energy and time you spend not focusing because you're thinking about the meeting?

Investor and entrepreneur Paul Graham explains this phenomenon in his article on the differences between manager schedules and maker schedules. For a maker, who spends their most productive hours creating new things (e.g. a writer or developer), a meeting unseats their focus. Before and after the meeting, the maker can't do their best work because their mind is clouded with the anticipation of the meeting and the process of resetting into the creative mindset afterwards.

I find one meeting can sometimes affect a whole day. A meeting commonly blows at least half a day, by breaking up a morning or afternoon. But in addition there's sometimes a cascading effect. If I know the afternoon is going to be broken up, I'm slightly less likely to start something ambitious in the morning. — Paul Graham

The true cost of saying yes is the total time and energy it takes away from other opportunities.

Think about the most important ways you spend your time. Your most important work, your favorite hobbies, quality time with friends and family.

When you're assessing the true cost of saying yes to something, think about those important activities as the bank account you're withdrawing from. A 15-minute meeting that stretches to an hour doesn't just take an hour from your day; it takes an hour of time you could be spending on your best work, or strengthening relationships with your favorite people.

Say "I don't" rather than "I can't"

The way you turn down requests matters. Changing just one four-letter word can help us say no (and stick to it) when temptations arise.

Writer and entrepreneur James Clear wrote about this fascinating study published in the Journal of Consumer Research:

The study split participants into two groups. Each was asked to repeat a different phrase when offered temptations.

One group was asked to say "I can't eat that" when offered a temptation. For instance, "I can't eat ice cream." Another was to say "I don't eat that."

After repeating these phrases, the participants left the room, thinking the study was over. They were each offered a chocolate bar or a granola bar. This was where the study really began.

Those who had said "I can't eat that" chose the chocolate bar 61% of the time. In contrast, the group that said, "I don't eat that" only chose the chocolate bar just 36% of the time..

Saying “I don’t” instead of “I can’t” decreased the likelihood that someone would choose the chocolate bar by nearly 70%.

A similar study followed a small group of women who were working on health and fitness goals. They were each given a different approach to overcoming temptations throughout the study period:

- Just say no (i.e. no real strategy).

- Say "I can't" (e.g. "I can't miss my workout").

- Say "I don't" (e.g. "I don't miss workouts").

After ten days, only 3 of the 10 "Just say no" participants had persisted with their goal for the whole period. Even worse, only 1 out of the 10 "I can't" participants stuck at it. But the group that was told to say "I don't" was much more successful - 8 out of 10 participants persisted with their goal.

Why is there such a dramatic difference between saying “I don’t” versus “I can’t”?

Researchers think that the way we frame our decisions can have a big impact on our future actions. Saying you can't do something is a reminder that you're being held back by an external restriction. Saying you don't do something reinforces the idea that you're actively making the choice to say no, regardless of external pressures. Not doing something becomes a part of your self-identity - you’re now someone who doesn’t do that thing - making it easier to resist future temptation.

You can use the same principle when faced with requests for your time. If there's an opportunity that takes a toll on your time and energy, saying “I don't do that” may be easier in the long run than saying “I can’t”. Framing a “no” as “I don’t” reinforces the idea that you’re actively choosing to prioritize something else instead. It also helps to set boundaries for future requests rather than a one-off “no” each time a similar request comes up.

Share resources instead of your time

For people who genuinely want to help others, saying no can feel selfish. If guilt is the barrier that is keeping you from saying no, try writer Alexandra Franzen’s approach.

When she has to say no, Franzen tries to help in another way. Her template for turning someone down via email looks like this:

Hey [name],

Thanks for your note.

I'm so proud of you for ___—and I'm flattered that you'd like to bring my brain into the mix.

I need to say "no," because ___.

But I would love to support you in a different way.

[Offer an alternative form of support here]

Thank you for being such a wonderful ___. I am honored to be part of your world.

[A few closing words of encouragement, if you'd like]

[Your name here]

According to Franzen, "the key to crafting a gentle "no" is to include an alternative form of support." This "alternative" should obviously be something that you are willing to give (or do)— because it is easier, less complicated, or less time-consuming, it doesn't cost money, or it just feels good for you to offer. Not something that takes more of your time.

The beautiful thing about this approach is that it maintains your relationship with whoever is requesting your help while at the same time maintaining clear boundaries for what you’re willing to spend your limited time and energy on.

Here are a few resources you can offer when you want to help someone without agreeing to their request:

- Suggest someone else who might be able to help.

- Offer to introduce them to someone you know.

- Share links to relevant articles or videos.

- Suggest books you've read that might be useful.

- Point them to any resources you've used yourself in the past.

Set rules ahead of time

Part of what makes saying no so difficult for me is agonizing over whether I should say yes or no. Even if I do say no, the time and energy I spend deliberating has already cut into my schedule whether or not I end up saying no.

You can overcome this by setting rules for yourself ahead of time. Similar to the idea of saying you don't do particular things, you can settle on what you do and when, to make it easier to decide whether to accept or deny requests in the future.

Author and computer science professor Cal Newport suggests making these rules in the form of an "attention charter" for yourself.

An attention charter is a document that lists the general reasons that you’ll allow for someone or something to lay claim to your time and attention. For each reason, it then describes under what conditions and how often you’ll permit this commitment.

This is particularly useful for those things you can't avoid completely (perhaps they're required for your work), but which suck your time and energy when you focus on them too much. For instance, social media, networking, or attending conferences.

Newport suggests setting up a charter that clearly outlines which activities you won't do at all, and what your limits are for other opportunities. For instance, you might say you don't attend any conferences outside your country. For conferences in the country, you might set rules like this:

- There must be at least three speakers you're excited about for you to attend a conference.

- And you attend a maximum of two conferences per year.

Having these rules laid out ahead of time makes it much easier to know what to say no to, and it gives you a framework for saying no. Rather than looking for an excuse or fumbling an awkward no, you can simply explain the rules you've set for yourself and how this request doesn't fit into them.

Or as Newport says:

The reason I suspect strategies like an attention charter work, is that it acknowledges that certain time fragmenting activities are necessary, but it gives you the hard limits you need to engage in these activities without losing control.

Each of these approaches has one thing in common: they involve planning how to act ahead of time.

Saying no is so uncomfortable and unnatural for us that we have to prepare ourselves for it. We need rules and structures to rely on because looking someone in the eye or talking to them on the phone and turning down their request can be nigh impossible without them.

If you struggle to say no as much as I do, do yourself a favor and spend some time to plan your “saying no strategy”. Use these approaches to plan how to respond to requests ahead of time, so you’re never caught off-guard. You’ll thank yourself when you’re enjoying that extra time and peace of mind that comes when you give yourself permission to say no.